8 habits to help you get through your PhD

Shabana Khan reveals the study tricks that helped her to battle through her doctoral studies

- Student life

Share

É«şĐÖ±˛Ą

For many, working towards a PhD is more than a stepping stone in their career – it’s a personal journey. I’m in the final stretch; it’s a stressful time, but despite that I’m feeling content and at ease with myself and the world around me.

For many postgraduates, the four years of intense independent research is a really stressful time. The process involves adaptation, independent thinking, continuous learning and constant responsibility for producing meaningful work and an original contribution to knowledge. This in itself is not only daunting but extremely exhausting, both mentally and physically.

On top of all that, it’s often really hard to explain to those around you what you’re going through. I was told many times that others wouldn’t be able to relate to my experience unless they go through it themselves.

It isn’t easy for family and friends to understand that you’re under constant pressure, facing challenges that you have to overcome over and over. That can leave you feeling emotionally, mentally and physically drained. Despite this, having supportive family and friends goes a long way in allowing you to successfully cope with the many phases of PhD study.

It's important to acknowledge the importance of your own well-being. This is often neglected while being in the PhD loop: conducting experiments in the lab, attending weekly meetings, obtaining and analysing data, preparing presentations, writing papers, writing the thesis and so forth. Thus, it becomes more important than ever to take care of ourselves during this busy time.

So here are eight habits that I developed during the course of my doctorate studies that not only helped me to better cope with the ridiculous amount of stress, but also transformed me into someone who could, in any given situation, look beyond the stresses and truly appreciate the journey (and still remain somewhat positive at the end of the day!).

Observing – rather than always taking action or reacting

Observe everything around you. From the smallest things to the bigger picture. But at the same time, remain detached from your surroundings rather than attached. This feeling of detachment allows for observance rather than an emotional response to what is happening around you. When you’re ready to respond, allow yourself to connect emotionally. Learning to detach and attach at will is so important in maintaining your well-being.

Reading –  read, read, read!

I find reading so relaxing that I would say it has become my therapy.

I need to get through a certain number of pages of the novel I’m reading every day to unwind and feel content. Reading has allowed me to reduce stress and anxiety and to feel a sense of  total detachment from the surroundings, and this in itself for me is therapeutic.

Limit coffee to the morning…

…and substitute with fresh mint tea in the evenings.

I’ve been hospitalised in the past for exceeding a healthy amount of caffeine intake to the point where the paramedics thought I was on drugs. Although that sounds ridiculous (and hilarious), I realised soon enough that seriously cutting back on the amount of coffee I drank during a hectic day in the lab, or prior to any deadlines, was necessary.

I now drink only one cappuccino in the morning on my commute, and an occasional second on a coffee break once a week. As for the rest of the day, I substitute with fresh mint tea, using fresh mint leaves –  just throw them into a cup and add boiling hot water with a splash of lemon. Inhaling the scent of fresh mint really takes away the day’s stress and helps me to unwind.

ł§·Éľ±łľ!

I was always of the mindset that my commute to and from the lab was so long that there wasn’t enough time in the evenings to relax, let alone to fit in exercise. So I did not prioritise it.

This led to an enormous build-up of mental stress, resulting in exhaustion: increased heart rate, low blood pressure and, eventually, anxiety and the feeling of being overwhelmed by  my experiments, my deadlines, my social life and my relationships.

The solution was to release that mental and physical stress. I decided to take on regular weekly swimming –  an hour session in the morning before going into the lab, no matter how busy I was. I get all the cardio I need, my body gets a workout without straining my joints, it helps my back, and most of all I enjoy it – it leaves me feeling content and more relaxed.

Don’t dwell on mundane tasks

One thing I’ve learned about myself is that I prefer to get the small things done and dusted (and quickly out of my way) than to leave them aside and worry about later.

I of course feel the need to prioritise the bigger, more important things first, but this approach works for me. It’s like decluttering my surroundings and my mind of things that are trivial, unimportant and mundane but necessary. So I clear my to-do list as quickly as I can and then move on to the tasks that require my time and attention.

Be creative

I’ve reconnected with my younger self, when my passion for art was fierce. I’d come home every day from school, and find myself working on new artworks every evening.

Either I was drawing, or learning new techniques to paint, or assembling creative leaving cards with pockets containing chocolate coins.

All the effort and passion that I used to put into my art sort of got pushed aside while I was studying for A levels and then my degree. Since deciding to specialise in the life sciences, I realised that the educational system divided up the sciences and the arts so drastically that it left no room for appreciating how much overlap the two have.

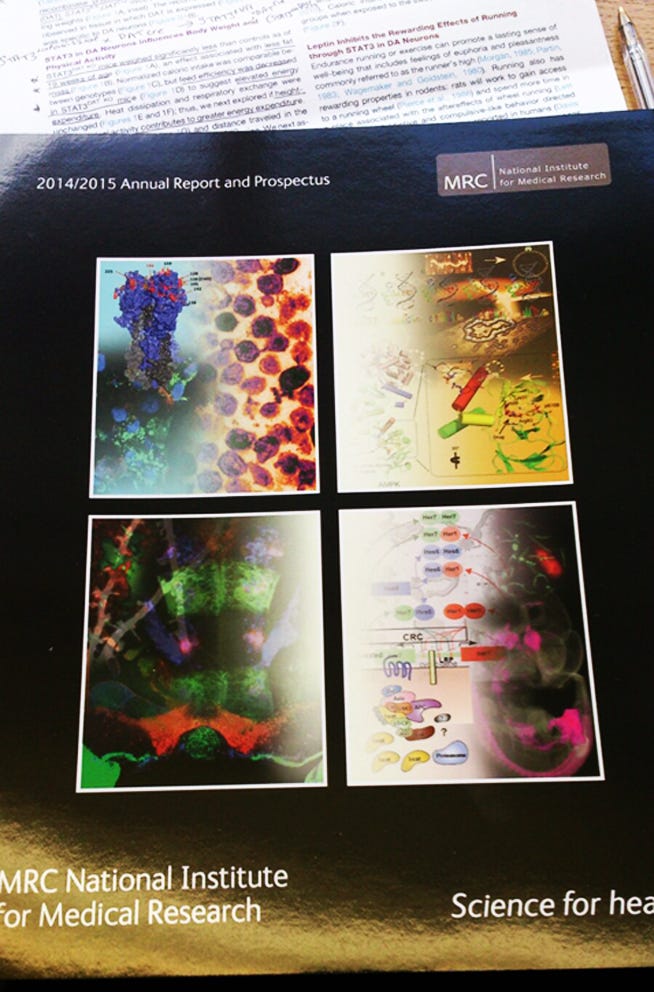

It wasn’t until I began conducting immunohistochemistry experiments in my undergraduate final-year research project at UCL that I once again began appreciating the inherent art that exists within nature.

Later on, as a first-year PhD student, I developed a deeper interest for what is now called SciArt. I now take images of my scientific research for art purposes and plan to submit an entry for the Art of Neuroscience 2016 competition, which is looking for striking visualisations related to the field of neuroscience in its broadest sense.

My scientific research image (bottom left) on the cover of a prospectus

Write regularly

You can read most of the time, but there comes a time when you’re compelled to write.

As a PhD student, you’re generally required to be constantly writing something or other. This starts with a three-month, then a 12-month progress report, and the more important “upgrade” report that gets submitted to the thesis committee.

Aside from this, you’re constantly updating abstracts for submission to international conferences . Mine, for example, was accepted to present at the Society for Neuroscience 2015 conference in Chicago.

Then comes scientific paper writing practice, which we all need by the end of our PhDs, and which can be solid training for future postdoctoral positions.

Finally, something I’m beginning now : writing my original contribution to scientific knowledge, after the endless experiments conducted in the lab over the past four years, into a single document called The Thesis.

Aside from all the scientific writing practice, beyond this I’ve made a point of writing outside of science and at a more personal, introspective level. Whether it be recording daily thoughts in short bursts, or a more elaborate written piece on my thoughts and ideas, I treat non-scientific writing as a sort of personal development exercise.

Get back to nature

N˛ąłŮłÜ°ů±đĚýis a source of happiness and peace in itself. The beauty of nature never ceases to amaze me. Observing the natural world is always an uplifting experience that allows you to surround yourself with positive energy. Distance yourself from that which is negative, whether negative people or negative atmospheres.

It is easy for another’s negativity to affect your own state of mind. Your own well-being is important.

Shabana Khan is a final-year neuroscience cell and developmental biology PhD student working at the Francis Crick Institute Mill Hill Laboratory in London.